Mutiny Philippines: The January Mutiny

Mutiny is a situation in which a group of people (such as sailors or soldiers) refuse to obey orders and try to take control away from the person who commands them (See Merriam-Webster definition of mutiny). Related words include insurgency, insurrection, rebellion, coup and coup d'état. In the Philippines, there is no shortage of mutinies and coups that may be tackled. This series is dedicated to that matter.

***

See the first part of this series by clicking here (The December Coup).

***

One month from today would be the 143rd anniversary of the most famous (or infamous, depending on the point of view) mutiny that was conducted in the Philippines during the 19th century. Such was the repercussions of this event that its effects on the 1896 Philippine Revolution was quite evident. Three of the chief figures in this event would be used as password in the Katipunan (KKK). This is the Cavite Mutiny launched on January 20, 1872 by some 200 soldiers and laborers at Fort San Felipe. Besides the slightly peculiar number that became famous quite recently for representing in numerology the expression of love (143), this article would attempt to look at the Cavite Mutiny which actually began with a "bang."

First of all, why January 20? The date is simply far away from Christmas, or Epiphany. However, it still takes advantage of the supposed festive, and therefore lax, mood of the people for the day was the beginning of the Feast of the Virgin of Carmel, Our Lady of Loreto. The only pitfall of selecting the date lies on the signal to start the mutiny. If one is to believe the accounts of the survivors, the supposed signal was the sound of a rocket from their expected allies in Manila. However, most feasts in the archipelago had to have fireworks, and the Feast of the Virgin of Carmel is no exception. Thus, the mutineers in Cavite mistook the fireworks as their expected signal from Manila. On January 21, the expected reinforcements did not arrive. Rather, there were the more numerous Spanish troops bent to quell the mutiny. Four of the mutineers died, including Sergeant La Madrid, who was said to have died due to gunpowder.

This signal would later be integrated by Rizal in his El Filibusterismo. It could be remembered that Simoun, the main character of the novel, designated a cannon that would fire at night. The loud sound produced by the cannon's firing would have begun the planned revolution, but this was not to be after Simoun discovered the death of Maria Clara. It could also be recalled that Simoun had contact with a pyrotechnics expert, accompanied by the student Placido Penitente. In his second attempt to launch his long overdue revolution, Simoun designated the explosion of the famous lamp containing nitroglycerin as the signal to begin.

Why Cavite Mutiny? That is, considering the mutiny only took place in a single fort among the many in Cavite. The supposed reinforcements of the mutineers from Manila may have not even existed. How about Fort San Felipe Mutiny, as compared to the more recent Oakwood Mutiny (2003)? Perhaps it was a propaganda technique of the Spanish to sensationalize the event. But, then again, how about the Novales Mutiny, which would also be tackled later in this series? No one dared to call it Manila Mutiny or something quite similar. The argument that the Novales Mutiny was composed of Creoles (mixed blood) and the Cavite Mutiny of natives will also not hold. There is no evidence that Andres Novales did not have native contingent in his 800 soldiers. Also, how can one explain the existence of the leader of the Cavite Mutiny, Sergeant Ferdinand La Madrid? It even seems that this sergeant was Creole. If new evidence surfaces that he really was of mixed blood, then this trivial question would be resolved.

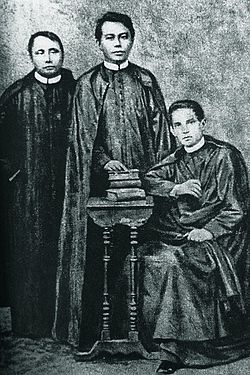

Why implicate the Gomburza? It has been known that the three native priests (Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos, Jacinto Zamora) had taken up the mantle of reform first launched by Father Pedro Pelaez in the 1860s. What was called for was the secularization of the parishes. The campaign resulted to the giving of friar-held parishes to regular priests, many of whom were native of origin. Around half of the parishes in and around Manila were already headed by native regulars by the 1870s. This threat to the friars and their hold in the Philippines made them suspected of organizing the failed mutiny, and this actually was proven in 1897. It cannot be denied that even certain men of God were bound to participate in the shadows of political affairs.

During the Philippine Revolution, Emilio Aguinaldo and his men captured two ranking friars who revealed their role in the Cavite Mutiny. Before the mutiny, a conference among heads of the orders were held. Issues discussed revolved on how to dispose Burgos and his fellow leaders in the native clergy. The plan they formed was to send out a secular priest disguised as Burgos. This priest would, in turn, pay some people eager to stage a coup in exchange of money. It is of no wonder, at this point, why many of the survivors of the mutiny would implicate Burgos as their supposed head. One would say Burgos was to be their "president," while another said that their aim was to set up Burgos as "king." The "star" witness, Francisco Saldua (said to be a messenger of Zamora to Burgos in three occasions), would even say during the trial that a certain Ramon Maurente contracted a United States fleet to aid the mutineers. That is, for 50,000 pesos. To think that the Crucera Filipina, the unfinished cruiser paid for by the Philippines in 1885, costed only 20,000 pesos, the supposed amount paid for by Maurente was very heavy indeed.

Rizal would subliminally present his own version of the story in Noli Me Tangere, wherein a fake revolution was launched by paid men to implicate the reformer Crisostomo Ibarra.

May it be organized by Spaniards or by Filipinos, by friars or by laborers, a Spanish military victory or not, the Cavite Mutiny remains a significant episode in Philippine History. The most recognized result of the event, the execution of the Gomburza, would produce a new wave of reformists known later as the "Sons of 72." The idea of reform is very potent that the words of a popular Filipino televangelist might hold true in this case: "Paano mo mapapatay ang ideya?" (How can you kill an idea?). And, it is of common knowledge that this was the generation of Jose Rizal, Apolinario Mabini, Marcelo H. del Pilar, Graciano Lopez Jaena, among others. El Filibusterismo itself was dedicated to the three priests.

Perhaps this verse in the Bible would fit best in this situation: "Many are the plans in the mind of a man, but it is the purpose of the LORD that will stand."

***

***

See the first part of this series by clicking here (The December Coup).

***

|

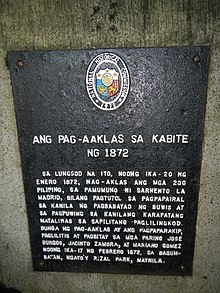

| Cavite Mutiny historical marker Photo courtesy of Wikipedia |

First of all, why January 20? The date is simply far away from Christmas, or Epiphany. However, it still takes advantage of the supposed festive, and therefore lax, mood of the people for the day was the beginning of the Feast of the Virgin of Carmel, Our Lady of Loreto. The only pitfall of selecting the date lies on the signal to start the mutiny. If one is to believe the accounts of the survivors, the supposed signal was the sound of a rocket from their expected allies in Manila. However, most feasts in the archipelago had to have fireworks, and the Feast of the Virgin of Carmel is no exception. Thus, the mutineers in Cavite mistook the fireworks as their expected signal from Manila. On January 21, the expected reinforcements did not arrive. Rather, there were the more numerous Spanish troops bent to quell the mutiny. Four of the mutineers died, including Sergeant La Madrid, who was said to have died due to gunpowder.

This signal would later be integrated by Rizal in his El Filibusterismo. It could be remembered that Simoun, the main character of the novel, designated a cannon that would fire at night. The loud sound produced by the cannon's firing would have begun the planned revolution, but this was not to be after Simoun discovered the death of Maria Clara. It could also be recalled that Simoun had contact with a pyrotechnics expert, accompanied by the student Placido Penitente. In his second attempt to launch his long overdue revolution, Simoun designated the explosion of the famous lamp containing nitroglycerin as the signal to begin.

Why Cavite Mutiny? That is, considering the mutiny only took place in a single fort among the many in Cavite. The supposed reinforcements of the mutineers from Manila may have not even existed. How about Fort San Felipe Mutiny, as compared to the more recent Oakwood Mutiny (2003)? Perhaps it was a propaganda technique of the Spanish to sensationalize the event. But, then again, how about the Novales Mutiny, which would also be tackled later in this series? No one dared to call it Manila Mutiny or something quite similar. The argument that the Novales Mutiny was composed of Creoles (mixed blood) and the Cavite Mutiny of natives will also not hold. There is no evidence that Andres Novales did not have native contingent in his 800 soldiers. Also, how can one explain the existence of the leader of the Cavite Mutiny, Sergeant Ferdinand La Madrid? It even seems that this sergeant was Creole. If new evidence surfaces that he really was of mixed blood, then this trivial question would be resolved.

|

| Gomburza: Gomez, Burgos, Zamora Photo courtesy of Wikipedia |

During the Philippine Revolution, Emilio Aguinaldo and his men captured two ranking friars who revealed their role in the Cavite Mutiny. Before the mutiny, a conference among heads of the orders were held. Issues discussed revolved on how to dispose Burgos and his fellow leaders in the native clergy. The plan they formed was to send out a secular priest disguised as Burgos. This priest would, in turn, pay some people eager to stage a coup in exchange of money. It is of no wonder, at this point, why many of the survivors of the mutiny would implicate Burgos as their supposed head. One would say Burgos was to be their "president," while another said that their aim was to set up Burgos as "king." The "star" witness, Francisco Saldua (said to be a messenger of Zamora to Burgos in three occasions), would even say during the trial that a certain Ramon Maurente contracted a United States fleet to aid the mutineers. That is, for 50,000 pesos. To think that the Crucera Filipina, the unfinished cruiser paid for by the Philippines in 1885, costed only 20,000 pesos, the supposed amount paid for by Maurente was very heavy indeed.

Rizal would subliminally present his own version of the story in Noli Me Tangere, wherein a fake revolution was launched by paid men to implicate the reformer Crisostomo Ibarra.

May it be organized by Spaniards or by Filipinos, by friars or by laborers, a Spanish military victory or not, the Cavite Mutiny remains a significant episode in Philippine History. The most recognized result of the event, the execution of the Gomburza, would produce a new wave of reformists known later as the "Sons of 72." The idea of reform is very potent that the words of a popular Filipino televangelist might hold true in this case: "Paano mo mapapatay ang ideya?" (How can you kill an idea?). And, it is of common knowledge that this was the generation of Jose Rizal, Apolinario Mabini, Marcelo H. del Pilar, Graciano Lopez Jaena, among others. El Filibusterismo itself was dedicated to the three priests.

Perhaps this verse in the Bible would fit best in this situation: "Many are the plans in the mind of a man, but it is the purpose of the LORD that will stand."

***

Have you enjoyed or been annoyed by the series? Comment and share. Kindly answer the year-long survey.

See the references by clicking here.

See the references by clicking here.

Comments

Post a Comment