Rizal foresaw it in 1891? (Southwest monsoon special)

|

| Jose Rizal Photo courtesy of Wikipedia |

Her fellow travelers had taken measures of defense by keeping up among themselves a lively conversation on any topic whatsoever. At that moment the windings and turnings of the river led them to talk about straightening the channel and, as a matter of course, about the port works. Ben-Zayb, the journalist with the countenance of a friar, was disputing with a young friar who in turn had the countenance of an artilleryman. Both were shouting, gesticulating, waving their arms, spreading out their hands, [6]stamping their feet, talking of levels, fish-corrals, the San Mateo River, of cascos, of Indians, and so on, to the great satisfaction of their listeners and the undisguised disgust of an elderly Franciscan, remarkably thin and withered, and a handsome Dominican about whose lips flitted constantly a scornful smile.

The thin Franciscan, understanding the Dominican’s smile, decided to intervene and stop the argument. He was undoubtedly respected, for with a wave of his hand he cut short the speech of both at the moment when the friar-artilleryman was talking about experience and the journalist-friar about scientists.

“Scientists, Ben-Zayb—do you know what they are?” asked the Franciscan in a hollow voice, scarcely stirring in his seat and making only a faint gesture with his skinny hand. “Here you have in the province a bridge, constructed by a brother of ours, which was not completed because the scientists, relying on their theories, condemned it as weak and scarcely safe—yet look, it is the bridge that has withstood all the floods and earthquakes!”

“That’s it, puñales, that very thing, that was exactly what I was going to say!” exclaimed the friar-artilleryman, thumping his fists down on the arms of his bamboo chair. “That’s it, that bridge and the scientists! That was just what I was going to mention, Padre Salvi—puñales!”

Facsimile of the first page of

El Filibusterismo

Ben-Zayb remained silent, half smiling, either out of respect or because he really did not know what to reply, and yet his was the only thinking head in the Philippines! Padre Irene nodded his approval as he rubbed his long nose.

Padre Salvi, the thin and withered cleric, appeared to be satisfied with such submissiveness and went on in the[7]midst of the silence: “But this does not mean that you may not be as near right as Padre Camorra” (the friar-artilleryman). “The trouble is in the lake—”

“The fact is there isn’t a single decent lake in this country,” interrupted Doña Victorina, highly indignant, and getting ready for a return to the assault upon the citadel.The besieged gazed at one another in terror, but with the promptitude of a general, the jeweler Simoun rushed in to the rescue. “The remedy is very simple,” he said in a strange accent, a mixture of English and South American. “And I really don’t understand why it hasn’t occurred to somebody.”

All turned to give him careful attention, even the Dominican. The jeweler was a tall, meager, nervous man, very dark, dressed in the English fashion and wearing a pith helmet. Remarkable about him was his long white hair contrasted with a sparse black beard, indicating a mestizo origin. To avoid the glare of the sun he wore constantly a pair of enormous blue goggles, which completely hid his eyes and a portion of his cheeks, thus giving him the aspect of a blind or weak-sighted person. He was standing with his legs apart as if to maintain his balance, with his hands thrust into the pockets of his coat.“The remedy is very simple,” he repeated, “and wouldn’t cost a cuarto.”

The attention now redoubled, for it was whispered in Manila that this man controlled the Captain-General, and all saw the remedy in process of execution. Even Don Custodio himself turned to listen.

“Dig a canal straight from the source to the mouth of the river, passing through Manila; that is, make a new river-channel and fill up the old Pasig. That would save land, shorten communication, and prevent the formation of sandbars.”

The project left all his hearers astounded, accustomed as they were to palliative measures.[8]“It’s a Yankee plan!” observed Ben-Zayb, to ingratiate himself with Simoun, who had spent a long time in North America.

All considered the plan wonderful and so indicated by the movements of their heads. Only Don Custodio, the liberal Don Custodio, owing to his independent position and his high offices, thought it his duty to attack a project that did not emanate from himself—that was a usurpation! He coughed, stroked the ends of his mustache, and with a voice as important as though he were at a formal session of the Ayuntamiento, said, “Excuse me, Señor Simoun, my respected friend, if I should say that I am not of your opinion. It would cost a great deal of money and might perhaps destroy some towns.”

“Then destroy them!” rejoined Simoun coldly.“And the money to pay the laborers?”“Don’t pay them! Use the prisoners and convicts!”“But there aren’t enough, Señor Simoun!”“Then, if there aren’t enough, let all the villagers, the old men, the youths, the boys, work. Instead of the fifteen days of obligatory service, let them work three, four, five months for the State, with the additional obligation that each one provide his own food and tools.”

The startled Don Custodio turned his head to see if there was any Indian within ear-shot, but fortunately those nearby were rustics, and the two helmsmen seemed to be very much occupied with the windings of the river.

“But, Señor Simoun—”“Don’t fool yourself, Don Custodio,” continued Simoun dryly, “only in this way are great enterprises carried out with small means. Thus were constructed the Pyramids, Lake Moeris, and the Colosseum in Rome. Entire provinces came in from the desert, bringing their tubers to feed on. Old men, youths, and boys labored in transporting stones, hewing them, and carrying them on their shoulders under the direction of the official lash, and afterwards, the survivors returned to their homes or perished [9]in the sands of the desert. Then came other provinces, then others, succeeding one another in the work during years. Thus the task was finished, and now we admire them, we travel, we go to Egypt and to Home, we extol the Pharaohs and the Antonines. Don’t fool yourself—the dead remain dead, and might only is considered right by posterity.”

“But, Señor Simoun, such measures might provoke uprisings,” objected Don Custodio, rather uneasy over the turn the affair had taken.

“Uprisings, ha, ha! Did the Egyptian people ever rebel, I wonder? Did the Jewish prisoners rebel against the pious Titus? Man, I thought you were better informed in history!”

Clearly Simoun was either very presumptuous or disregarded conventionalities! To say to Don Custodio’s face that he did not know history! It was enough to make any one lose his temper! So it seemed, for Don Custodio forgot himself and retorted, “But the fact is that you’re not among Egyptians or Jews!”

“And these people have rebelled more than once,” added the Dominican, somewhat timidly. “In the times when they were forced to transport heavy timbers for the construction of ships, if it hadn’t been for the clerics—”

“Those times are far away,” answered Simoun, with a laugh even drier than usual. “These islands will never again rebel, no matter how much work and taxes they have. Haven’t you lauded to me, Padre Salvi,” he added, turning to the Franciscan, “the house and hospital at Los Baños, where his Excellency is at present?”Padre Salvi gave a nod and looked up, evading the question.

“Well, didn’t you tell me that both buildings were constructed by forcing the people to work on them under the whip of a lay-brother? Perhaps that wonderful bridge was built in the same way. Now tell me, did these people rebel?”[10]“The fact is—they have rebelled before,” replied the Dominican, “and ab actu ad posse valet illatio!”

“No, no, nothing of the kind,” continued Simoun, starting down a hatchway to the cabin. “What’s said, is said! And you, Padre Sibyla, don’t talk either Latin or nonsense. What are you friars good for if the people can rebel?”

Taking no notice of the replies and protests, Simoun descended the small companionway that led below, repeating disdainfully, “Bosh, bosh!”

Padre Sibyla turned pale; this was the first time that he, Vice-Rector of the University, had ever been credited with nonsense. Don Custodio turned green; at no meeting in which he had ever found himself had he encountered such an adversary.“An American mulatto!” he fumed.

“A British Indian,” observed Ben-Zayb in a low tone.“An American, I tell you, and shouldn’t I know?” retorted Don Custodio in ill-humor. “His Excellency has told me so. He’s a jeweler whom the latter knew in Havana, and, as I suspect, the one who got him advancement by lending him money. So to repay him he has had him come here to let him have a chance and increase his fortune by selling diamonds—imitations, who knows? And he so ungrateful, that, after getting money from the Indians, he wishes—huh!” The sentence was concluded by a significant wave of the hand.

|

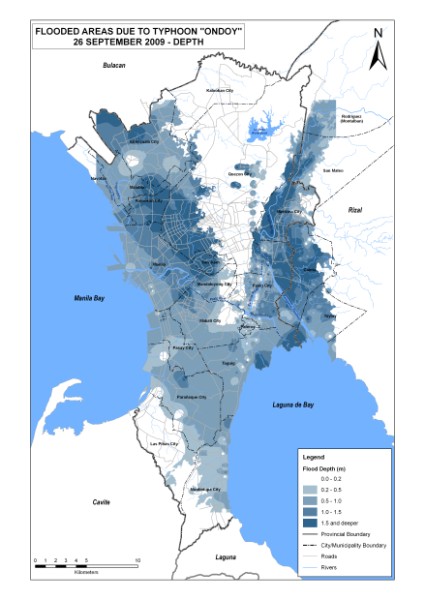

| Extent of flooding during Ondoy in 2009 Photo courtesy of srdp.com.ph |

No one dared to join in this diatribe. Don Custodio could discredit himself with his Excellency, if he wished, but neither Ben-Zayb, nor Padre Irene, nor Padre Salvi, nor the offended Padre Sibyla had any confidence in the discretion of the others.

In the above excerpt, it is apparent that Rizal had already thought of digging a Manila version of the Suez Canal. He envisioned it as both an entrepot of consumer goods in Asia and a flood control canal. Also, once a canal was bored out from Manila to Laguna, his home province would absolutely be a developing province like Manila. Imagine that? Had we had not learned much in urban planning more than a century? Also, if this was indeed a foresight from Rizal, where did he get his ideas on this issue? Had he also thought of the reverse flow spillway that would go through Laguna and Quezon? Thinking all of these, is it not fair to say that even Rizal's El Filibusterismo was a novel well researched?

***

Have you enjoyed or been annoyed by the series? Comment, and share. Kindly answer the year-long survey.

See the references here.

***

[Disclaimer: While some content may offend or cause disagreement with some readers, it must first be taken to mind that the author does not have access to the entire Rizal fountain of sources. Therefore, whatever analyses and conclusions made here are made as adequate as possible and are only built from the available evidences, sources and theories the author has access. Also, since only few editing, mainly grammatical, was made since this series was first written in 2012, then it is yet to be subjected to change. Any correction is welcome, but copying without permission is being frowned upon, since this blog is not under any Creative Commons Attribution. Thank you for reading the Filipino Historian.]

See the references here.

***

[Disclaimer: While some content may offend or cause disagreement with some readers, it must first be taken to mind that the author does not have access to the entire Rizal fountain of sources. Therefore, whatever analyses and conclusions made here are made as adequate as possible and are only built from the available evidences, sources and theories the author has access. Also, since only few editing, mainly grammatical, was made since this series was first written in 2012, then it is yet to be subjected to change. Any correction is welcome, but copying without permission is being frowned upon, since this blog is not under any Creative Commons Attribution. Thank you for reading the Filipino Historian.]

Comments

Post a Comment