Nansha Conflict: Contending for Kalayaan Islands

|

| The Murillo Velarde Map (1734) Photo courtesy of Murillo Velarde Map |

Before Spratly

The Spratlys was named after British captain Richard Spratly (1802-1870) by the British Admiralty, who first sighted Spratly Island itself (only one part of the archipelago) in 1843 and actually visited the area in 1864. Of course, this "discovery" of the Spratlys is based on the European standpoint. Zhao Rugua (Chao Ju-kua, 1170-1228) mentioned the islands in his work Zhu fan zhi (Chu fan chi) as Qianli Changsha (or Qianli Zhongsha, lit. A Thousand Li of Sands). Li is a unit measuring distance known also as the Chinese mile. The distance covered by one li varied across time (anywhere between 300 meters and 700 meters). However, the name Changsha shall later be given by the People's Republic of China (PRC) to Macclesfield Bank, a sunken atoll far from the actual Spratlys. Indeed, the Spratlys itself was called Nansha, which suggests that Zhao may have never reached the Spratlys proper. In 1834, the Vietnamese included the area in their maps as Truong Sa. The name remains to this day, at least in the Vietnamese point of view. The Philippines, then under Spanish colonial rule, also had maps which include the area. Among the earliest would be the Murillo Velarde map. Charted in 1734, it labeled what is now Scarborough Shoal as Panacot (lit. frightening). The name predates the "discovery" of the shoal by the East India Company ship Scarborough in 1784, headed by Captain Philip D'Auvergne. This suggests that the Philippines had explored the islands even before the Europeans were able to do so, but may have not managed to record it as extensively as the Europeans or the Chinese.

|

| Map of the Spratly Islands today Photo courtesy of Wikipedia |

Richard Spratly died in 1870, but the efforts to claim the region had just begun. Another British captain, James George Meads, visited the islands in the 1870s and was said to have claimed it for himself. However, this remains to be proven as this claim only appears later through his son Franklin Meads, who established the so-called Kingdom of Humanity in 1914. Unlike Spratly, there is apparently no recognition by the British Admiralty to the supposed feat of Meads to explore the area. Still, descendants of Meads like Josiah and Morton Meads continue to pursue their claim to the area even if it remains to be in vain. Besides the British, the Germans also tried to explore the area in 1883. When China protested, Germany apparently backed down.

The oldest legal text that the PRC may use to reinforce its claim to the archipelago is the Sino-French Convention at Beijing in 1887, seeking implementation of Article III of the Treaty of Tientsin in 1885. However, while the French excluded the area from its claim as it colonized Indochina, it did not automatically mean that the Spratlys is for China to take, nor did they take the chance to do so. Although the islands east of the 105th degree east are "assigned to China," it did not exactly mean that all islands in the east can be taken. The text may suggest that both sides knew what they were talking about (that is, the "contested points" of which the Spratlys are not even part of), and thus only designating a demarcation line. Apparently, China did not gain any new territory in the east of the line, the Spratlys or whatever. It lost territory in the west of the line, which were definitely incorporated in French Indochina. In fact, Chinese maps in 1928 do not include the Spratlys. In addition, the French asserted claims to the area in 1930. Either the Chinese do not know the exact boundaries drawn in the treaty, the French had never let go of the islands anyway, or neither side cared about the islands. It is indeed too far from any of these two countries. Whatever the case, it shall only be Chinese maps in 1947 which shall include the islands in Chinese territory. It is this 1947 map, the "Location of the South Sea Islands," that would give precedence to the so-called Nine Dash Line (later evolved into a Ten Dash Line in 2013) which covered more than 90% of the entire South China Sea (or West Philippine Sea). Of course, since the Chinese are yet to actually visit the islands, they simply renamed the islands already explored by the British. Meanwhile, the Philippines under American colonial rule also did not lay claim to the islands during this time (the Treaty of Paris in 1898 only included as far as 116th degree east as part of the Philippines, while the Spratlys were in the 114th degree east). As for the First Republic (1898-1901), there has been no provision in the Malolos Constitution concerning national territory. Miguel Malvar, President Emilio Aguinaldo's successor, did lay claim to the Marianas and the Carolines in the east of the Philippines. However, there has been no substantial evidence of official interest further west where the Spratlys are located. In addition, the Philippine Commonwealth (1935-1946) also did not extend claims to the archipelago, which by that time was already being claimed by the French, even though the geographical proximity is obvious and the constitution had a provision on national territory.

After the Second World War

During the Second World War, the Japanese occupied Indochina. The islands were used by the Japanese as staging points for the invasion of the Philippines (1941) when they constructed naval bases in the area in February 1939, perhaps a precedent being followed later by countries building installations in the region to date. After the war, the San Francisco Conference in 1951 took away control of the archipelago from Japan. However, with no clear successor to claim it, the door was open to anyone who would take the chance. While the Chinese only charted the islands on their maps as of 1947, Filipino explorer Tomas Cloma (1904-1996) had "discovered" the islands for the Philippine standpoint in the same year. Nine years later, in 1956, Cloma declared the seven islands he managed to occupy as Freedomland with himself as its chief. It has been widely accepted that the Spratlys are composed of at least fourteen (14) islands, and the Spratly Island itself was not part of Freedomland. While he did send his declaration (or "notice") the world over, no state took his claim seriously. Not even the Philippine government. Even at this time, no other country can legally claim the archipelago at least according to international law. Before 1958, national territory can only extend up to three miles (6 kilometers) from the coast. The Spratlys is beyond three miles from any neighboring country, and it is separated by large trenches. Therefore, it is legally regarded as international waters. In the first United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1958, this was extended from three miles to twelve miles (22 kilometers). Even so, the Spratlys are still beyond any national territory and remained to be international waters. The second UNCLOS in 1960 did not reach any new agreement. As for Cloma, he was forced to surrender his claims over the islands to the Philippine government in 1974. This acquisition served as basis for the creation of Kalayaan Municipality in 1978 though Presidential Decree 1596, signed by President Ferdinand Marcos. Of course, the name Kalayaan was not new. It was attributed to President Elpidio Quirino, the first Philippine president who knew of Cloma's exploration.

Law of the Sea in force

|

| Map showing overlapping claims to the Spratlys Photo courtesy of Wikipedia |

| Northrop F-5 Photo courtesy of Wikipedia |

Potential of the islands

One may ask: why is there so much competition in claiming these islands? These are some points which outline the potential of the Spratlys.

|

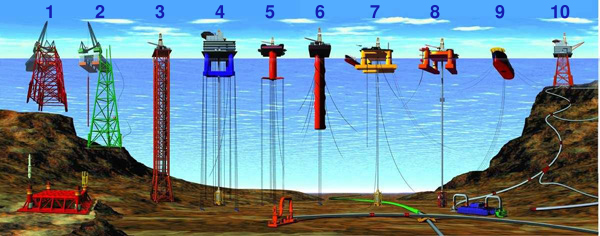

| Types of offshore oil and gas structures Photo courtesy of Wikipedia |

- Petroleum: The area has yet to be explored fully in terms of oil reserves. However, there has been confidence in the existence of such in the area. The Chinese, for instance, say that more than 105 billion barrels of oil and 25 billion cubic meters of natural gas lay below the Spratlys. To compare, the entire oil reserves in Asia (excluding West Asia or the Middle East) is 47 billion barrels as of 2011. So far, only the Philippines has been able to exploit these resources, at least publicly speaking. In 1979, the Philippine National Oil Company (PNOC) opened Nido-1 and had an initial output of 40,000 barrels per day. In 1980, it reached a total production of 12 million barrels of oil. This, however, did not last beyond the Marcos administration. In 2001, the Malampaya gas field began operation and it continues to this day. It has an average output of 1 million cubic meters of natural gas per day.

- Fish: As of 2001, around 20% of fish production of the Philippines come from the Spratlys. It was increased Chinese incursion in the area that decreased its output. Still, thus far, only the Philippines has been able to benefit substantially from fishing in the area. Of course, the Chinese have been using fishermen to legitimize its continued presence in the Spratlys. Whether these fishermen are really fishing in the area or are used for other purposes (such as exploring the area by having radars and other detection equipment installed on their boats), it remains to be seen how much fish China actually gain from the Spratlys. As of 2011, China recorded a total of 66 million metric tons of fish output for the year, while the Philippines had 5 million metric tons.

- Tourism: This remains to be seen. Still, the Spratlys is not as typhoon-prone as other parts of the Philippines which are in the typhoon belt. Besides, the Philippines had once declared intentions to push through with the development of the area as a tourist spot.

- Trade: Some $5.3 trillion worth of goods annually pass through the trade routes where the Spratlys are situated, of which around a fifth involved United States trade. Control of the area would decide the balance of trade, if not the dynamics of the economies, in the region. Of course, this figure is being disputed as soon as it was released. While there is concern for freedom of navigation, there are other trade routes being used in the Asia-Pacific region that do not pass through the area of conflict, but the trade routes that pass through the area is indeed the most convenient in the region, if not the cheapest.

Chengdu J-7

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia - Military: In the Second World War, the Japanese used the area as a staging point in invading the Philippines. The archipelago's worth for "forward" or "external" defense remains to this day, especially considering the construction of airstrips and installations in various points such as in Thitu (Pag-asa Island), Itu Aba (Taiping Island), Spratly Island (Truong Sa), and Fiery Cross Reef (Yongshu). Geographically speaking, the Spratlys is "within range" of any claimant. Perhaps only China is the exception, depending on the capability of the attacker. For instance, a Chengdu J-7 aircraft has a combat radius of 850 kilometers and can therefore strike against any other country neighboring the Spratlys. The J-7 is not even the most advanced fighter the PLA Air Force has. In addition, the airstrip developed by China at Fiery Cross Reef (the largest built in the area so far) is able to accommodate bomber aircraft. It puts every major city within the orbit of the Spratlys in peril to be bombed. For instance, the Xian H-6 has a combat radius of 1,800 kilometers. Again, like the J-7, the H-6 is not the most advanced bomber the PLA Air Force may offer. Thus, it shall prove dangerous if any one claimant manages to control the islands and develop them into effective military installations.

Update as of December 2016: At least twice after this article was published, the Chinese did fly the Xian H-6 bomber over the disputed area, the same aircraft mentioned in this article. Although not the most advanced of the Chinese bombers, it is capable of carrying nuclear weapons.

***

Do you like this article? Kindly comment and share.

What did the next Presidents after Marcos do, like Cory Aquino and FIDEL RAMOS ( who plundered the AFP modernization budget). To hell with these loathsome animals!! 😈😈😈

ReplyDelete