Cagayan's Last Stand? Conflict and Resolution of the 1582 Japanese "samurai invasion"

In 1582, a formidable Japanese force of at least 600 samurai pirates (wokou or wako) raided Cagayan, which was ultimately fended off by a significantly smaller Spanish force of 60. Or so the story goes, as featured by recent articles on the matter, including that of men's magazine Esquire Philippines. Some accounts even say it was 1,000 Japanese against 40 Spanish. This led to the claim of what was perhaps the only recorded battle between a European force and Japanese samurai during the early modern period. There was even a game derived from this battle. Except that there was more to the narrative than meets the eye. What had really happened in this so-called "samurai invasion" of the Philippines?

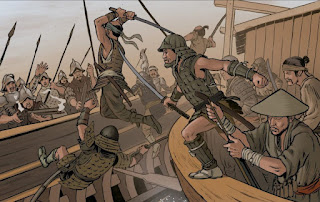

|

| Japanese pirates board a Spanish vessel Photo courtesy of Las Espadas Del Fin Mundo |

Analyzing the geopolitical position of the Spanish Empire in Asia

While it was also in recorded history how conquistadores of the 16th century managed to pull off victories despite the numerical inferiority of their troops, such as that of Hernan Cortes against the Aztecs or Francisco Pizarro against the Incas, their initial experience in the Philippines was not as successful. Instead of being regarded as gods, they suffered defeat, as noted in the Battle of Mactan. It was not until the Spaniards gaining local allies did the fortunes shift to their favor. Then again, even by 1582, the position of the Spanish colonial government was not in solid footing. Eight years earlier, in 1574, the Chinese pirate Limahong (or Lin Feng) attacked the colonial capital of Manila itself. Had not the Ming court went after Limahong's fleet at the same time he fought the Spanish, one could only speculate how differently the colonization process would have been. Meanwhile, in 1578, the Spanish fleet had used its strength in gaining a temporary triumph against the Sultanate of Brunei, then ruled by Seif ur-Rijal (or Saiful Rizal). Victory was not complete because Seif ur-Rijal, who was targeted because of his formal ties with the local Manila elite, eventually returned to power. The Spanish lost any political influence they exerted in Brunei by 1581.

As the Spanish consolidated power in its only colony in Asia thus far, it had only managed to focus its efforts in select settlements they have established. A quick glance at the founding dates of cities and towns would indicate the progress they have achieved. Their influence was even more diffused as one moved farther away from the capital. Cagayan, for instance, would not have an established colonial government until 1583. The said founding is known today as Aggao Nac Cagayan. More so, Spanish hegemony over the Philippines has been challenged. The 1529 Treaty of Zaragoza placed the archipelago within Portuguese territory, but the Spanish still pursued colonizing the islands anyway. When the Iberian Union placed Portugal under the Spanish crown in 1580, a new European challenge arose with the emergence of the Dutch, which declared their independence from Spain. While it would not be until 1600 when the Dutch would directly attack the Philippines, the Dutch threat encouraged the Spanish to strengthen its claim in the southern parts of the archipelago, mainly Mindanao. If the experience from Brunei taught the Spanish anything, any military victory they obtain would only reap benefits if they actually create settlements in the area, a lesson they meant to apply by 1596 with a fort established in Cotabato. An attack from the north would have been the last thing the Spanish wanted. This was the situation when the so-called 1582 Cagayan battles occurred.

|

| Ming depiction of a Luzon inhabitant Note the European outfit at this time Photo courtesy of Cai Ruxian |

At least two Spanish sources provided details on the matter. One was from Juan Bautista Roman, royal representative to Manila, and the other was from Governor General Gonzalo Ronquillo de Peñalosa. A critical analysis of their works, however, would reveal not only disagreement with the widely-circulated story of what seemed like a David versus Goliath victory, but also conflict between the accounts themselves. In a letter penned in Cavite on June 25, 1582, Bautista informed the viceroy of the arrival of six soldiers from the command of Captain Juan Pablo de Carrion just the day prior, June 24. Carrion was said to have launched his fleet of one galley, his flagship Saint Joseph (Sant Jusepe), and five frigates from Vigan to Cagayan. Bautista added it would be a 35-day journey. While en route, Carrion's fleet had an encounter with a Chinese pirate, whose ship they boarded with 17 soldiers. It would not be until they reached Cape Bojeador (located in Ilocos Norte, with Bautista saying it was Borgador) when the Spanish would engage against a Japanese pirate ship. Sixty arquebusiers (infantrymen with long guns called arquebus) fired from the Japanese ship, while 200 more pirates boarded the Spanish galley, which they achieved through grappling hooks. Somehow, the Spanish managed to win this engagement, with 18 survivor pirates surrendering. The galley's captain, Pero Lucas, was among those who were killed in the Spanish side.

Upon proceeding to Cagayan River, they found a fort and 11 more Japanese ships. Instead of engaging, however, Bautista noted the fear among Carrion's men, who urged their leader to return to Manila. Not only could they not enter the Japanese holding, sailing back and forth in the process, they appeared to have experienced water shortage for being at sea longer than they expected. Six soldiers were sent to find a water source, but they lost their way. It would not be until they met some of the local (indio) crew from Carrion's fleet would they have a lead. The discharged crew would relate how they were removed from service due to lack of supplies. Also, the six soldiers found out that Carrion's flagship, manned by 60 soldiers and an unidentified number of sailors who remained in service, was attacked by 18 Japanese sampans (champan, or fishing boats), the pirates supposedly numbering 1,000. The galley, already short in supplies and labor, also suffered leak "everywhere" and lost three of its cables due to a storm. As if the misfortune of the fleet was not enough, it was said the Chinese crew of the relief ship from Cavite to help Carrion launched a mutiny and killed 10 of the Spanish soldiers. The six soldiers got to know this story from a surviving sailor who escaped by swimming away from the ship, which probably meant the relief never made it.

Bautista ended with an appeal to the viceroy to send a reinforcement of 1,000 soldiers, noting that while the Governor General was disposed to send aid, he only had 70 soldiers available in the city.

The contradiction of the account could be examined in three major points. First, the story did not come from the soldiers' firsthand experience. As far as Bautista's narrative was concerned, they survived to tell the tale because they were lost. Whether or not Carrion purposely abandoned them, the soldiers may have never known. They only got to report anything because of the local crew who were sacked, presumably because Carrion's fleet could no longer provide for their maintenance, and a sailor who managed to survive the mutiny of Carrion's supposed relief. If Carrion's fleet was undermanned, it was a conscious choice considering their supplies. Therefore, the events described here might have happened long before June of 1582. In an undated contemporary account called "Relation of the Philippine Islands" (to be distinguished from Miguel de Loarca's similarly titled Relaciones), presumed to be written around 1586, Carrion's venture was placed in March of the same year. However, with unknown authorship and dating, it could not be verified if the Relations was a report based on firsthand knowledge. Still, Bautista himself already noted a month's journey from Ilocos to Cagayan, and that meant smooth sailing, not accounting the number of naval engagements Carrion's fleet had to experience. It might have even happened earlier than March 1582. Second, the strong appeal for the viceroy's assistance did not imply the situation was under control. Instead, it appeared to be a desperate call of help. The first two engagements with one Chinese ship and one Japanese ship were clearly indicated as wins, even though there seemed to be a conscious choice to deflate the Spanish casualties, but Carrion's gloomy conditions thereafter did not show any victory. They did not even willingly engage the enemy. The Japanese pirates, as the story went, took the battle to them.

|

| Wokou (wako) pikemen fighting Chinese soldiers Photo courtesy of Wako-zukan (Illustrated Scroll of Attacking Japanese Pirates) |

The Governor's report from Manila, meanwhile, was not as detailed, but it was sent later than the representative's. In a letter to King Philip II (Felipe, the namesake of the colony) dated July 1 of the same year, Ronquillo had a similar story as Bautista's. Carrion's fleet encountered two ships near Cagayan, one Chinese and the other Japanese. It was not stated that they were affiliated, consistent with Bautista's report. There was also a storm which struck Carrion's fleet upon reaching Cagayan. He also called for as many reinforcements as possible, albeit with no definite number, emphasizing that he had already made the request before but was not heard. However, that was where their commonalities end. Claiming that he only got the news yesterday, presumably sometime between June 29 and June 30, Ronquillo's picture was not as bleak as Bautista's. In the first Japanese ship Carrion encountered, not only did they manage to kill the pirate commander, but the Spanish just lost three soldiers. There was no mention of the slain captain. If Bautista already deflated the Spanish losses, Ronquillo took it a step further. Also, instead of being attacked by Japanese pirates in Cagayan, Carrion was said to have established a settlement as basis for fortifications, and instead of going up two leagues (11 kilometers) into Cagayan River as Bautista had noted, Ronquillo reported Carrion's fleet going as far as six leagues (33 kilometers). Cagayan River is the longest river in the Philippines, having a total length of 505 kilometers. Ronquillo added that Carrion had not only attacked the Japanese because he lacked the men, and so the Governor had the opportunity to impress that he was sending whatever reinforcement he could to help in Cagayan. Ronquillo and Bautista also differed in the size of the pirate fleet. The Governor General indicated there were only six Japanese ships, of which the first Japanese ship they encountered was part of. This was around half of the pirate fleet size in Bautista's account. There was no story of how the supposed relief ship sent from Cavite suffered from a mutiny.

If one would believe Ronquillo's account, his information should have been more updated and direct. It was the Governor General assuming responsibility for sending out the fleet, and so the assumption would be Carrion was reporting to him. Then again, for a narrative that was supposedly firsthand knowledge, it seemingly lacked the details of Bautista's account. Whether it was a conscious choice or not, Ronquillo appeared to be doing whatever he could to downsize the gravity of the situation. Regardless, his urgent appeal for reinforcements contradicted with claims of victory and settlement. The founding of Spanish Cagayan would happen a year later, on June 29, 1583, albeit in an earlier report by Ronquillo's predecessor, Doctor Francisco de Sande, a settlement was already established in Cagayan as early as 1579. The delay may imply various reasons, and not necessarily a resounding Carrion triumph over the pirates. Carrion waiting it out for the wokou to move on and founding his fort over the foundations of the wokou holding might be within the range of possibilities on how the campaign developed, if the differences of the two accounts had to be reconciled. Ronquillo's claim of fortifications in Cagayan, however, would be put under more scrutiny when considering how the 1586 Memorial to the Council by his successor Doctor Santiago de Vera and the Real Audiencia recommended the construction of a fort in Cagayan against "Chinese and Japanese robbers" who operate every year. At any rate, it was probably not Carrion who first settled in Cagayan, if indeed his mission met success despite the wokou raids, and the settlement in Cagayan may have been existent before the recognized date of 1583. Then again, it could have not been any time earlier than 1575, for Governor General Guido de Lavezares (Lavezaris) would only have sent an expedition at this time to explore Cagayan. There might also be the issue of where Carrion's fleet was actually attacked. It was said Carrion was able to set up camp in Lal-lo for settling Nueva Segovia, which was further up the Cagayan River, but the available secondary sources only mention Aparri, some 40 kilometers north of Lal-lo. Interestingly, none of the primary sources (Bautista, Ronquillo, and the undated Relations) gave details on where these battles should have occurred, if they were indeed victories. Then again, if Carrion's fleet was attacked off Aparri, it would have rationalized the need to find water to drink, as Bautista had earlier mentioned. Otherwise, they could have tapped Cagayan River itself if they somehow managed to settle there. Meanwhile, Ronquillo as governor might not be as trustworthy as well. Attorney-General Gabriel de Rivera (Gavriel de Ribera), who accompanied Miguel Lopez de Legazpi's expedition, found sufficient evidence for a formal complaint against Ronquillo during his governorship. Bishop Domingo de Salazar, the first bishop of Manila, also found fault in Ronquillo's appointments. However, Ronquillo would not see how the process would play out as he died in 1583.

What may add context to this would be Ronquillo's earlier letter to the king on June 16, 1582. He noted how pirate ships from Japan came in the period between 1580 and 1581. Like in Bautista's account, Ronquillo talked of sending six ships. However, instead of 60 in Bautista, there were 100 soldiers with Carrion in Ronquillo. This mission was supposed to establish a settlement in Cagayan called Nueva Segovia, which explains why Ronquillo was firm to claim that Carrion successfully settled there. This also creates an assumption that Carrion may have had more people with him, other than the numbered soldiers and the unnumbered sailors. Ronquillo, however, contradicted his later account by saying in this report that there were 10 Japanese pirate ships coming to the Philippines, instead of the later seven ships. His chronology also created some confusion. It appeared that Carrion's fleet was dispatched as a response to a coming Japanese threat, but Ronquillo already noted how the Japanese pirates already did damage in their raids during the past two years. Had the Governor General acted too late at this juncture, for there were only two weeks difference between his first and second letters to the king? Were the reports from the sea arriving too slow? In that case, would the delay in reporting be circumstantial evidence that things were not going as well as they initially hoped? Also, Ronquillo's report ran counter with the undated Relations. While they both agreed on Carrion's fortifications, the Relations spoke of an even more fantastic battle. The Japanese pirates, 600 in number, attacked the 80 strong Spanish force because negotiations supposedly broke down. Its report of one casualty on the Spanish side, who was "killed by accident", would make Ronquillo's claim modest in comparison. The Relations would cite another contemporary, the Portuguese missionary Francisco Cabral, to boast of how Japan feared the Spanish military prowess. That could have solidified the story of the Cagayan victory, but not only did it disagree with both Bautista and Ronquillo, the undated Relations also appear to be an outlier among its supposed contemporary sources, such as the 1586 Memorial to the Council. The undated Relations also seemed to contradict itself, for while claiming victory for Carrion in 1582, it also narrated how the Spanish efforts of settlement in Cagayan were not successful.

|

| A depiction of the 1582 Cagayan battles Photo courtesy of Las Espadas Del Fin Mundo |

Nonetheless, while these accounts come from sources of questionable reliability, they somehow agree on yet another thing: there was no Japanese samurai invasion. There was even no indication that they were samurai at all. Most importantly, the primary character of the supposed pirate army, Tay Fusa (Tayfusa, Tayfuzu, Taifuza, or Taifu-sama), was not mentioned in any of these sources. Even the undated Relations, which mentioned of the Japanese pirates being in Cagayan under orders of their "king," did not name the pirate "general" leading them. An addition by later sources? Perhaps incidentally, taifu in Japanese meant typhoon or storm. Thus the saying taifu ikka or "the storm has passed." Was there a connection in the provenance? A reference to the Cagayan storm that damaged Carrion's fleet? Being familiar with the typhoon season of the Philippines, however, would probably push back the possible real date of the Cagayan engagements to as far back as 1581, since the archipelago would have been seldom struck by storms in the first half of the year. It was even rarer in March, as the Relations claimed the date was. In the month of March, the start of the nation's hot dry season, only one storm enters Philippine territory in two to three years. Meanwhile, the two reports by Bautista and Ronquillo were made in June-July of 1582, and it would have taken time for them to receive news from the sea, considering how only two weeks prior, Ronquillo just wrote about sending Carrion's fleet to Cagayan.

In retrospect, the wokou (wako), or "small pirates", did not always mean Japanese. In one Ming account, it was said only three out of ten would have been Japanese. The Chinese Limahong, who himself had Japanese subordinates such as Lieutenant Sioco (Shoko?), could also be regarded as wokou. The two accounts were in line with other contemporary records of wokou. They were not considered part of the Japanese regular forces at the time, particularly the Sengoku period, although they were integrated in naval operations, such as in the case of Yoshitaka Kuki serving under both Oda and Toyotomi. They did not wear as much armor as samurai, which was rationalized considering their battle tactics. Many of them used spears and pikes, called yari in Japanese, similar to what the wokou in Cagayan used. They also used bows and arquebuses, but mainly in close range combat wherein the accuracy was better. It was rare for them to use swords, or katana in Japanese. If wokou did use swords, they were likely to be dual wielders, either using two large swords (odachi) or a large sword paired with a short one (kodachi). This would have been logical considering the process of producing katana, which involved weeks of forging. If there were samurai among their ranks, they would likely to have been ronin, or masterless. Considering this, it might have been farfetched for a Japanese lord to send out an invasion force to settle as far as the Philippines. The Sengoku period already featured enough coastal action to keep their navies busy in Japanese waters, and an overseas victory in largely unknown territory may not mean much in a time of civil war. Note the likes of Luzon Sukezaemon or Justo Takayama Ukon. Whoever Tay Fusa really was, or where his allegiances lay, it was not really known. Then again, despite having notoriety for their raids, the wokou were far from excellent naval operators. Speed was of the essence in their campaigns, and so it reflected in their military organization. It was rare for them to operate in extremely large numbers, say Limahong, and if they did use other large ships such as junks, they were likely to have been captured than built with their own expertise. Some of them even burn down their own ships when facing defeat. The wokou raids were everywhere in the West Pacific area, and not only in the Philippines, so much so that the Chinese issued haijin (sea ban) as early as the 14th century.

Then again, where could the interpretation of government-sanctioned piracy be traced from, if not from Japan or China? Enter the privateers of Europe. By the time of this wokou threat, English naval officer Francis Drake had successfully circumnavigated the world from 1577 to 1580 upon being commissioned by Queen Elizabeth I. He was knighted in 1581, and later made Vice Admiral during the Anglo-Spanish War. His piratical career against Spanish shipping earned him a rather straightforward nickname from them: El Draque, the Dragon. Until then, the Pacific was widely seen as part of the Spanish sphere of influence despite the Treaty of Zaragoza, as Spain had colonies on both the western and the eastern parts of the ocean, so Drake's incursion sent shockwaves to the establishment. Even King Philip placed a bounty over his head. And he was not the only one who was being commissioned to harass the sea lanes. Spain had to operate their own "pirate hunters", such as Treasure Fleet architect Pedro Menendez de Aviles, to counter such piracy.

Significance of the battle that never was

If there was any naval victory to commemorate at this juncture, perhaps it would be that of Cape Bojeador, not the engagement in Cagayan proper, but it would not be as grand as the popular version of the story. While the famed heroic last stand of the Spanish forces in Cagayan may have not happened in our history as it was popularized, it still provided insights on the status of Spanish colonization in the Philippines a decade after Manila was established as the colonial capital. If the threat of raiding Japanese pirates, assuming they were Japanese at all, shook the Spaniards enough to ask for significant reinforcements, then one could only imagine the precarious situation of their establishment, and how they relied on the local population to strengthen their position. Meanwhile, it remains unlikely for any Japanese lord to send out samurai or wokou to invade the Philippines as early as 1582. Toyotomi would attempt to make a tributary out of the Philippines, but that would come a decade later, when Japan was more stable as a country and Toyotomi could afford to launch the invasion of Korea. Of course, conclusions in history are at best tentative. When new evidence surfaces on the matter, a reexamination might be merited.

Comments

Post a Comment